Benchmarking law school rankings against expectations, performance, and rankings tactics

A look at how expectations are set, and whether evidence and data explain why we're right--or wrong

Whenever the USNWR law school rankings are released, there are typical cries of “how did X school move to Y?” This usually reflects a kind of mental benchmark—schools X ought to be at not-Y but ended up at Y. That could be because there is an expectation that the school should be higher or lower than it is.

We all have expectations, then about where school “should” be. Of course, what USNWR uses for its own methodology does not necessarily reflect one’s expectations.

But schools do change over the years, and there are ways of helping reset some expectations against actual schools’ performance. Likewise, there are rankings-related tactics that some schools use that are largely—or only—explicable in terms of USNWR rankings metric performance, which can also help explains rankings outcomes.

Let’s start with two ways to look at schools’ performance: employment outcomes and peer reputation. Then we’ll look at a third: which schools’ tactics may be helping drive rankings changes.

Law school performance and employment outcomes

It is always challenging to evaluate employment outcomes because of the many competing ways people may value employment outcomes. There’s no question the recent changes to USNWR rankings significantly value raw quantity of legal jobs—the more jobs your graduates have, the better your ranking. Of course, this obscures some—yes, disputed!—classifications of “quality” of legal jobs.

One way to measure recent changes in how some law schools have fared is to measure not simply their overall employment outcomes, but their improvement in “elite” employment outcomes. Here, I look at placement in law firms with at least 101 attorneys and federal judicial clerkships. I averaged the last two years of such placement (the Classes of 2022 and 2023, consistent with the benchmark USNWR uses in its overall employment rankings) with the outcomes five years ago (2017 and 2018).

There’s no question that Howard has a very strong, and improving, performance in “elite” employment outcomes, but there is not a correlating rise in the rankings—in other words, it would appear to be underappreciated. It’s also possible to suggest better employment markets in Los Angeles, Florida, and Utah have contributed to rising fortunes for some schools. The University of Utah has seen a significant improvement in its overall USNWR ranking, and there’s no question it tracks the increase in its elite employment outcomes. On the other side, USC is lower than it has been traditionally ranked in the USNWR rankings, despite having one of the highest elite employment outcome climbs in the last five years.

Law school performance and peer reputation scores

Another useful metric is to evaluate changes in the “peer reputation score.” This survey of law school deans, associate deans, appointments chairs, and recently-tenured faculty offers a window into how law faculty around the country view schools. This survey receives much less weight in the new rankings methodology, but it still offers one assessment of reputational quality, and how that might relate to overall law school quality. Here are some of the biggest movers in what one might label the top 1oo-ish schools in the last five years.

Unsurprisingly, Texas A&M has had the single fastest and greatest rise in the USNWR rankings in history, and it likewise sees a massive increase in its peer reputation score. Utah, too, has seen a rise. Regent has gone from a more marginal school in the rankings to a school around the top 100. And Wayne State likewise has seen a significant rise in recent years. It is possible, then, to acknowledge that while one might be “surprised” to see some schools climb in the rankings, it is less of a surprise to many peers who fill out these surveys.

In contrast, the three biggest underperformers are three of the most elite law school—some reputation halo effects seem to be lagging, for whatever reason, in recent years.

Law school performance and rankings tactics

I have written a lot about the USNWR law school rankings over the years. A lot. And there’s often conversation—speculation, or complaints, or what not—about which schools are “doing” something with the USNWR law school rankings. That is, there are a handful of levers schools can pull to affect the rankings. Which ones are doing so most effectively? Or, perhaps slightly differently, which ones are doing so most aggressively?

For much of the rankings, we know what metrics matter and what schools do. They can press for employment for all students; they can help bar exam preparation; they can target certain admissions medians.

But these are things all law school do, some more effectively than others.

A different question is which schools are doing so most aggressively. That is, looking at metrics and law school behavior that are explicable largely on the basis of USNWR rankings, what are schools doing?

Now, “explicable largely” is a dicey category. But over the years, I’ve found five categories that, I think, are largely explicable as rankings gambits.

First, unusually high academic attrition. Some modest academic attrition is inevitable—there are chances taken on students in the admissions process that just don’t work out. But at some schools, attrition is consistently higher than peer schools and higher than admissions benchmarks suggest. That looks more like an effort to remove low-performing students who might adversely affect bar passage or employment outcomes, as those outlier schools stand apart.

Second, conditional scholarships. Law schools that have “conditional” scholarship and remove a significant number of scholarships from second- and third-year law students can create an artificially high scholarship budget for incoming first-year students, knowing that many will lose them in the second year. Law students enter with cognitive biases that they believe they will overperform. What percentage of law students lose their conditional scholarships each year?

Third, school-funded employment and graduate school for recent graduates. These categories are not necessarily “bad” employment outcomes, per se. But USNWR recently changed its methodology to give these categories “full weight.” We can compare to see which schools saw dramatic upticks in these categories of employment (school-funded jobs and graduates pursuing advanced degrees) over their historical norms.

Fourth and fifth, disparate UGPA and LSAT medians and 25th percentiles. Schools want to obtain a relatively high median, because that is what USNWR counts in the rankings. Schools that see significant disparities between the medians and the 25th percentiles are “chasing” the medians as the credentials lag for the bottom half of the class—and schools that saw compression between the 75th and 50th but significant gaps between the 50th and 25th, more so. (This is hardly a “new” tactic and one widely accepted in many admissions circles—of course, there are reasons to think alternative admissions models may offer their own benefits.)

I took these five categories and looked at the top 100-ish law schools (i.e., those schools most likely to be pursuing rankings figures). I then developed a composite score of these five equally-weighted and scaled categories, against on a 20-80 scale, to see which schools landed as among the most aggressive in pursuing rankings tactics, and which were among the least aggressive. This, too, can help explain some of the movement in the rankings.

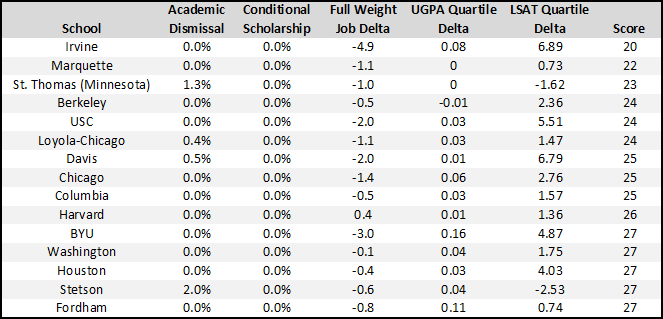

The chart below identifies the most aggressive with these five categories: academic dismissal rate; conditional scholarship removals; change in newly-defined “full weight” jobs (here, change in graduates in school-funded jobs or pursuing advanced degrees over historical norms); delta in UGPA quartiles (i.e., the bigger the number, the higher gap between 50th and 25th percentiles of UGPA than 75th and 50th); delta in LSAT quartiles.

You can see a variety of approaches here. Some, like Texas A&M and UNLV, have essentially no attrition, no conditional scholarships, and no meaningful change in employment outcomes—but their incoming class figures weigh heavily. Others, like Washington University and George Mason, rely on both admissions and jobs.

Now, again, it’s useful to consider these figures in context—Texas A&M and San Diego, for instance, have seen improvement in the rankings, but they have also seen significant improvement in their peer scores, suggesting, of course, it’s not all tactics doing the work.

How about schools that have done the least in these domains?

Many of these schools saw declines in the types of “full weight” positions compared to historical norms. They often have very balanced incoming classes. They have essentially no dismissals or conditional scholarships. It is no surprise to see many elite schools here. But it is also telling to see USC—recall, it has seen a sharp rise in high quality employment outcomes—or Harvard—its employment figures are not necessarily as high as one might expect—on the list. That is, it is possible to conceive of some schools that could be doing more to enhance their rankings.

Reexamining expectations

In sum, this is not to say any particular approach is “good” or “bad.” Again, this post is an explanatory one. There are different assumptions people bring to the rankings. They have assumptions about where schools “should” be. That could be based on anchoring effects from the past, or beliefs about schools that do not reflect reality or recent conditions.

There are ways in which USNWR masks some schools’ quality, and some ways in which the USNWR is manipulable. There are ways in which some categories of USNWR data reveal a lot about a school’s current position or status in the overall world of legal education, even apart from the USNWR composite score or overall ranking. There are ways in which the rankings mask what schools are doing.

But it is worth reflecting that when an assumption arises that a school is “too low” or “too high,” what does that actually mean? And is there some evidence that could undermine—or, perhaps, reinforce—that assumption?