On ABA accreditation: a proposal to increases costs at schools, which falls disproportionately on a handful

A new, expansive curriculum requirement would increase costs generally but burden a few schools the most

This is the third of a series of posts about proposed changes to Standards 303, 304, and 311.

In my first post, I noted that the ABA has a formal policy against micromanagement of a law school curriculum. It is possible to overcome that policy with an adequate justification. The ABA has not done so, which I demonstrated in my second post.

Even if a new requirement could be justified, it would still need to be weighed against the costs of the proposal. The costs are significant, and the proposal fails to grappled with those costs.

The explanations in the Proposal with respect to cost rely on few and inadequate sources.

The following conclusory sentence sums up the Council’s position: “Further, the Standards Committee’s research indicated that an increase in required experiential learning credits is not likely to lead to higher tuition and, especially given its delayed implementation, may not lead to higher costs for a number of law schools.” There is no citation to this “research” and no explanation as to how the Council reached an assessment that it is “likely” (or how likely it is) not to lead to “higher tuition,” and how it “may not” (but in some circumstances, may) lead to higher costs for a “number” (unknown in quantity) of law schools.

Importantly, however, this sentence acknowledges that it may lead to cost increases. As this Comment will demonstrate, those costs are likely to fall disproportionately on the most resource-lacking law schools.

And the Committee recognized:

it was “acutely aware of the Council’s concern about the current cost of legal education and the barrier to entry it poses”

it knew of “the burden it places on students during their studies”

it acknowledged “the limiting effect it has on career choice for many students,”

the context “particularly in this moment of uncertainty about student loans”

that “most costs for law school are fixed and continuing, with any change in requirements potentially leading to increased costs”

These are five, major concerns that received essentially no attention because of four, rather flat conclusions that there would “likely” not be “higher tuition” (which is quite different from higher costs).

First, the Committee offered an “initial survey” with responses from just 83 law schools (less than a 50% response rate), and with nothing more rigorous than the simple assessment as follows: “53% (44/83) of those law schools able to meet a requirement of 9 experiential learning credit hours without needing to expand their current course offerings. A further 19.3% (16/83) of the responding law schools would need to expand their current course offerings but believed this expansion was manageable.”

This is an inappropriate use of this data. The Council’s final Proposal:

(1) is an increase from 6 to 12 (100% increase) instead of an increase from 6 to 9 (50% increase) as the survey instrument asked;

(2) requires at least 3 of the units to be clinical or field work, which the survey instrument did not ask; and

(3) did not indicate that it intended to exclude first-year experiential learning.

In other words, the survey indicated some modest feasibility from a handful of law schools for a Proposal that is, in at least three respects, materially less onerous than the one this Council is actually proposing. Yet, it still relies on this same survey data. Even here, the survey also shows:

(4) at least 18/83 schools (21.6%) suggest even a 3-unit increase in any experiential learning would not be “manageable”;

(5) the word “manageable” implies an acceptable increase of cost, heretofore undescribed, as identified by individual survey respondents; and

(6) more than 100 law schools have not formally weighed in.

This piece of data is, frankly, non-responsive to the actual Proposal and cannot be used in support of its Proposal.

Second, the Council states, “Other research on the costs of providing experiential courses shows that, while law clinics are more expensive than larger enrollment courses and field placements, the costs of clinics are largely in line with those of the seminar courses law schools widely provide.”

Here, the Council has actually, affirmatively admitted that experiential courses are “more expensive.” This is a significant concession. It is particularly troubling to use it as a leverage point to require these smaller, more-expensive courses. There is no universe in which the Committee would require law schools to ensure graduates have “seminar courses” as a part of their curriculum. But that is precisely what the Committee proposes. The question is not whether small courses are more expensive than large ones (they are). The question is, should such courses be required. (There is more to consider about the relationship between seminars and experiential education, which I discuss infra, Part III.B.)

So it is a non-sequitur to admit that clinical education costs similar to smaller courses. The concession that it costs more than a modal law school course is significant enough to consider whether there are sufficient benefits to require it.

Third, “Professor Robert Kuehn explains that schools that provide or require more experiential courses, including law clinics, are not charging more in net tuition to their students than schools that do not provide or require these experiences.”

This explanation is, respectfully, a significant, and sometimes misleading, gloss on the literature cited in this single, four-page essay from 2016 labeled an “expla[nation],” as cited in the proposal.

In that explanation (cited to purportedly assess costs in 2025), one study cited from the ABA is from 1980—before I was even born.

Another study is purported to claim that for one school, “tuition income generated by law clinic courses came very close to meeting the actual instructional costs to the school.” The calculations in that article demonstrate the opposite. It reflects a calculation that a full-time clinical instructor would generate around $128,000 in net tuition revenue from the entire semester of teaching a clinic, but could generate another $114,000 from teaching a single two-unit Ethics course with a 50-student enrollment. In other words, if clinical faculty taught more students, the value proposition would be more feasible.

A comparable financial model suggests that net tuition revenue from teaching a 70-person 4-unit Property course, a 50-person 3-unit Evidence course, and a 20-person 2-unit Property seminar would yield nearly $500,000 in net tuition in that 2009 model of tuition at one institution. The model suggests that clinical education is about four times the price, unless clinical faculty add to their responsibilities—or unless schools choose to significantly underpay clinical faculty.

One more item from this explanation, because it is not my effort to provide a line-by-line rebuttal of evidence that this Proposal never meaningfully considered—it is only to highlight its summary is misleading and has not been adequately considered. Professor Kuehn writes, “Most recently, Pepperdine announced that beginning with next year’s class, students must graduate with at least 15 credits of experiential course work, yet the school increased tuition for 2015 by less than its average increase for the prior three years.”

As a former Pepperdine professor, I can assure you this summary misleads the reader. Pepperdine’s “experiential” requirement is not “experiential” as defined by the ABA, at least as introduced and understood in 2015. Instead, its nine units beyond the six ABA units includes four units of first-year legal writing—in short, a pre-existing requirement labeled “experiential” and one that does not meet the ABA’s definition (nor would it be permitted in a proposal that bars first-year experiential learning from fulfilling the requirement). The remaining five units can be fulfilled through work on a law journal or in moot court advocacy competitions, any courses (including simulation courses) so labeled by the dean (regardless of the ABA’s label), and one unit for any “52.5 hours of legal work under the supervision of a lawyer, paid or unpaid.” In short, myriad, flexible, often pre-existing ways to achieve the “experiential” requirement that do not map onto that ABA’s cabined definition—and certainly that do not require clinical work or a field placement.

This “explanation” offers no effort to evaluate confounding variables such as whether the school generates revenue from its clinics; whether the school has endowed or independently subsidized its clinics; whether all experiential courses have equivalent costs; and so on. “Experiential” education, after all, includes simulation, field placements, or clinical, which have three very different models of cost.

In short, the brief explanation cited, with all due respect, includes dated studies, elisions, and misreading of the evidence. The Council should rely on studies themselves to assess costs, not explanations that purport to summarize studies—which it has failed to do.

Fourth, the Council believes that law schools can “shift resources . . . (rather than adding resources)” and “make faculty hires to meet the revised Standard.” The acknowledgement that law schools will need to hire faculty is a significant one, one of the biggest costs of law schools. And the notion that schools must hire faculty without needing to add resources, or that a “shift” in resources could happen in just three years, is a strange conclusion.

The Proposal acknowledges that experiential education more generally, and clinical education in particular, costs more than other forms of instruction. That cost should counsel special hesitation in placing a new requirement upon schools, even if it could be justified (which, as Part II demonstrates, the evidence does not support). But more importantly, the burdens of the cost of the Proposal will likely fall disproportionately on a handful of schools with fewer resources.

The most significant costs of the Proposal will likely fall disproportionately on law schools with fewer resources.

The data about existing clinical and field placement education reveals something stark. High-resource schools already invest significantly in clinical education and field placements. Low-resource schools do not. This mandate is not just an increase in cost for legal education. It is an increase in cost that disproportionately fill fall on the law schools with the fewest resources in the United States.

It is important to note that “high resource” and “low resource” are not meant to signify whether these schools are “better” or “worse.” It is simply to acknowledge that some schools have more resources and some fewer. Many excellent law schools serve their communities with few resources, to the benefit of those communities and to the students who can often graduate with lower debt loads. But it is to recognize, once again, that legal education is not monolithic.

Measuring this is a challenge. But one way to evaluate school with more or with fewer resources is to evaluate schools with higher or lower “peer reputation” scores as measured by U.S. News & World Report. That score is the result of a survey of law school deans, administrators, and faculty. It is fair to say that the schools at the “top” of that rating, which is scored on a 1 to 5 scale, have a significant amount of resources (think Yale, Harvard, and Stanford). Higher-rated institutions are typically competing for the most elite students and faculty and spending the most money. In contrast, lower-rated institutions are typically more regional in nature, are serving a smaller geographic community, and are not competing to “climb” the rankings. While this measure is only a rough approximation, it can help assess the investments of these institutions.

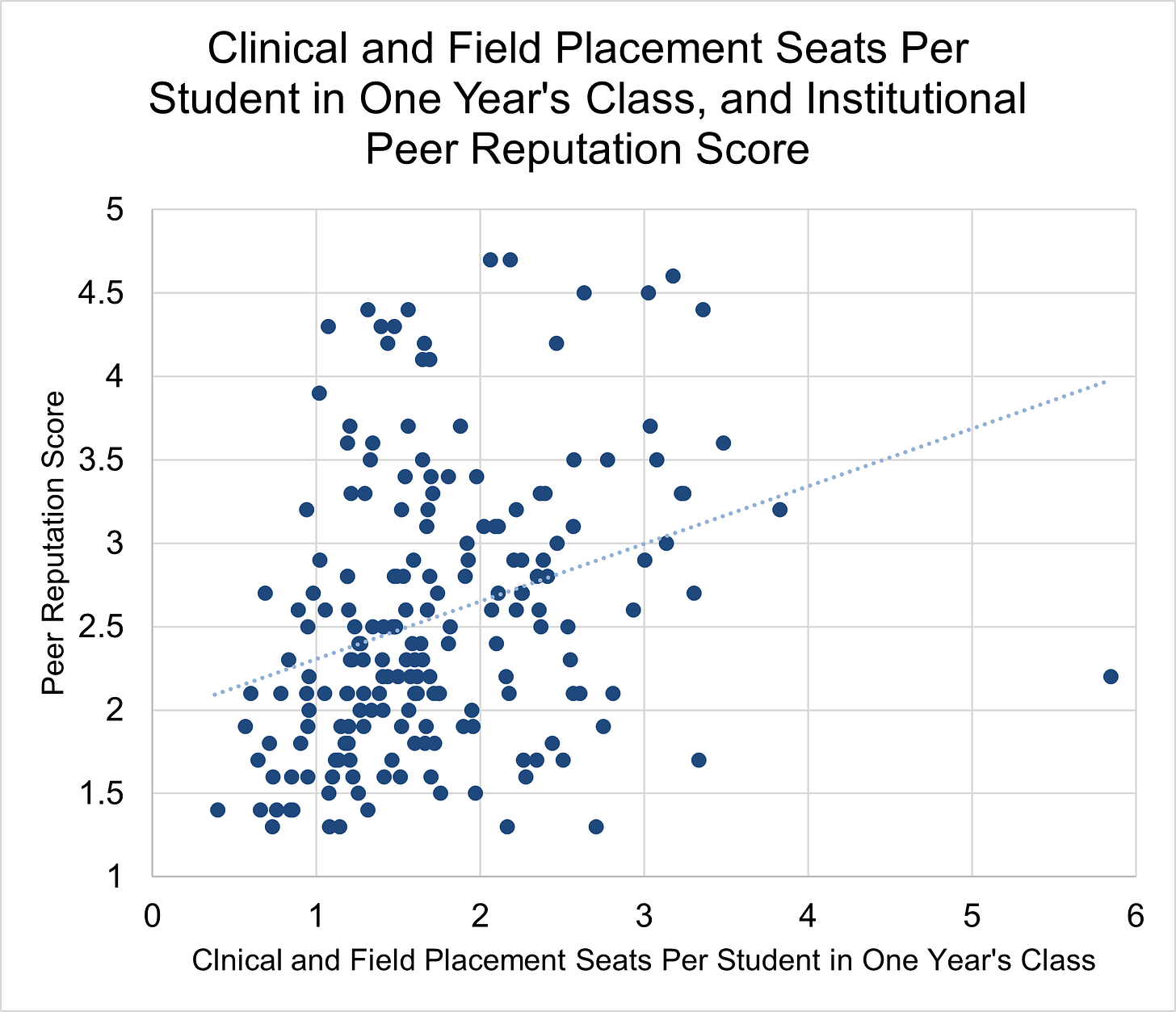

The ABA collects data on clinical and field placements available at each institution. That is, we can measure how much existing capacity there is at each law school. We can look at that capacity against the size of one year’s class (i.e., one-third of the overall enrollment). This measure is also a rough approximation, because class sizes may grow or shrink from year to year. But the goal is to assess whether each student could fulfill this requirement based on existing annual capacity.

The chart above allows some important observations. The first is to note that many schools do have existing capacity in clinical and field placements. (A perfect 1.0 total clinical field placement seats per student is probably too small, and a figure closer to 1.5 or 2.0 is perhaps more realistic in assessing whether there is adequate capacity to account for varying class size, student preferences, schedule conflicts, and the like.) The second is to note that as reputation score rises (that is, as an approximation for resources rises), clinical and field placement capacity rises.

Most of the “elite” law schools (e.g., those over a 3.5 peer reputation score) have at least 1.5 seats per student; many have 2 or 3 per student. In contrast, many schools with fewer resources perform poorly on this metric. Many of the schools ranking most marginally in the peer reputation score category have a very low capacity.

This chart alone calls for more scrutiny of the Council’s Proposal. If the costs fall disproportionately on the institutions with the fewest resources, it is unclear what effect this would have on legal education. Would some schools, unable to afford the new costs, simply close? Would schools with lower tuition because they are not “chasing” “elite” students or faculty suddenly have a new expense that would require the increase in tuition that falls disproportionately on students?

The costs are not merely financial. The costs would also be curricular.

Perusing some of the schools who are ranked at the lower end of the institutional peer reputation scores and who have some of the fewest experiential course offerings, it becomes apparent why that is the case. St. Thomas University requires 90 units to graduate. 51 of those are required courses, leaving just 39 as electives. Texas Tech requires 90 credit hours. 56 are required, leaving just 34 as electives. Barry University requires 90 credit hours. 57 to 62 are required, leaving just 28 to 33 as electives.

Law schools can, rightly and understandably, choose different curricular paths. These are just a few schools that have a sizeable required curriculum. Adding to that requirement places disproportionate disruption among these types of schools. When there are so many required courses, it becomes harder and harder to provide the flexibility to meet additional ABA mandate. It is challenging to schedule courses with enough flexibility for students to meet both the school’s requirements and the ABA’s requirements. And that might mean the school’s own requirements must give way—essentially, forcing them to restructure their curriculum. While many “elite” law schools have a fairly small required curriculum and could more easily adapt to an ABA mandate, many other schools do not.

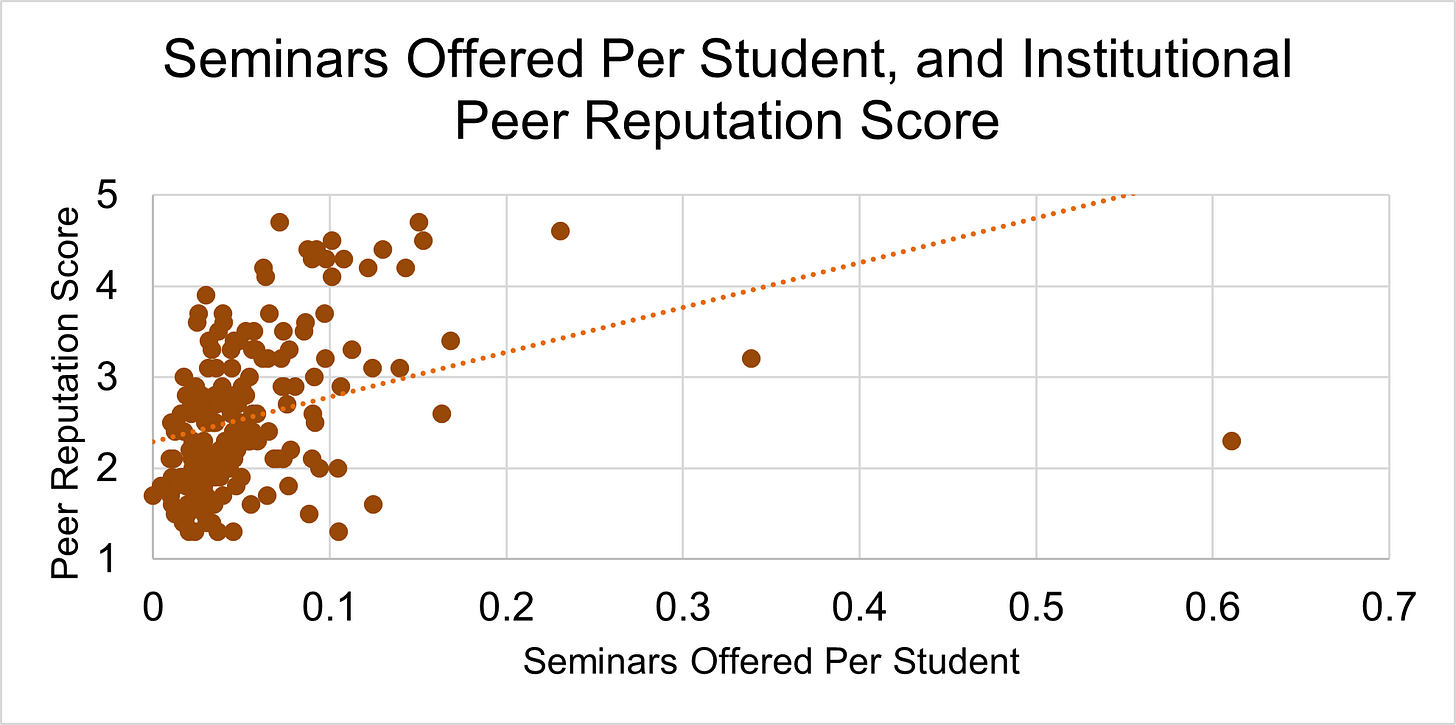

In some of the public discourse, some language has been used to suggest that the tradeoff is between law school “seminars” and clinical education. And with all due respect to the statements from faculty at institutions like the University of Florida—“The debate over the experiential credit requirement also reflects the longstanding tension between clinical and doctrinal teaching, said University of Florida Levin College of Law clinical professor Sarah Wolking. ‘The critics are doctrinal or podium professors,’ she said. ‘These are people who feel threatened by the idea that nobody is going to fill their niche seminars.’”—that is not the case.

We can use the same kind of data for seminar courses and compare them to institutional peer reputation sore. (For this, I used seminars per student rather than per one-third of the class, because seminars could, in theory, be offered anywhere in the curriculum and students might take several of them. While the numbers on the axis change, the relationship between class size and peer score remains the same.) And again, we see similar trends. The most resource-rich institutions have the most seminars. Those schools with fewer resources offer fewer of them. Given the substantial required curriculum at many of these lower-ranked institutions, the scarcity of seminars is no surprise.

In short, resource-rich institutions have more clinical opportunities, more externship opportunities, and more seminars. Those institutions with fewer resources have fewer of all three types of opportunities.

A few concluding words

Higher education is experiencing a period of extraordinary and costly disruption at the moment. Universities are making significant budget cuts for 2025-2026, with some universities cutting expenses between 5% and 10%. A “demographic cliff” approaches, which threatens future enrollment. Congress agrees that student loans from the federal government should be capped and are increasing taxes on endowments. Artificial intelligence and large language models may well alter the nature of the legal profession and the enterprise of legal education altogether and require significant changes in law school curricula.

This Proposal is undoubtedly well intentioned. It aspires to make law schools a place where professional development can occur better. It relies on myriad statements over the years about the value of a particular kind of educational experience. But this is a time where higher education needs to be more flexible, more nimble, more creative, and more diverse than ever. The Proposal admits it will increase costs at institutions. It lacks the evidence to justify this change. And it certainly lacks the evidence to depart from the Council’s longstanding position that law schools should manage their curriculum, not the Council.

And if the ABA continues its efforts for proposals that lack evidence, increase costs, and increase homogenity in legal education, it may well be time to reconsider its role as accreditor for purposes of who is eligible for the bar exam.