Projecting the 2026-2027 USNWR law school rankings (to be released around April 2026)

We can look at next year's trends with recently-released data

My USNWR law school rankings projections have been pretty good—but hardly perfect. They are better at spotting directional trends (i.e., is a school going to climb or fall significantly, or stay about the same?) than landing on a precise ranking figure. But why not keep trying. I modified my own internal metrics a bit, error corrected a few things, and will try again.

Fifty-eight percent of the new USNWR law school rankings turn on three highly-volatile categories: employment 10 months after graduation, first-time bar passage, and ultimate bar passage. USNWR has tried to smooth these out by using a two-year average of these scores. (This results, roughly, in about half the volatility for a particularly good or bad year at a school, but it also means those effects are felt twice as long.) Those categories are also entirely based on publicly-available data.

Because USNWR releases its rankings in the spring, at the same time the ABA releases new data on these categories, the USNWR law school rankings are always a year behind. This year’s data include the ultimate bar passage rate for the Classes of 2020 and 2021, the first-time bar passage rate for the Classes of 2022 and 2023, and the employment outcomes of the Classes of 2022 and 2023.

We can quickly update all that data with this year’s data. And given that the other 42% of the rankings are much less volatile, we can simply assume this year’s data for next year’s and have, within a couple of ranking slots or so, a very good idea of where law schools will be. (Of course, USNWR is free to tweak its methodology once again next year. Some volatility makes sense, because it reflects responsiveness to new data and changed conditions; too much volatility tends to undermine the credibility of the rankings as it would point toward arbitrary criteria and weights that do not meaningfully reflect changes at schools year over year.) Some schools, of course, will see significant changes to LSAT medians, UGPA medians, student-faculty ratios, and so on relative to peers. Some schools have significantly increased school-funded positions after the change in the USNWR methodology. Likewise, lawyer and judge scoring of law schools appears to be more significantly adversely affecting the most elite law schools, and that trend may continue. And some schools are much more aggressive in their tactics to “chase” the rankings.

But, again, this is a first, rough cut of what the new (and volatile) methodology may yield. High volatility and compression mean bigger swings in any given year. Additionally, it means that smaller classes are more susceptible to larger swings (e.g., a couple of graduates whose bar or employment outcomes change are more likely to change the school’s position than larger schools).

If you are inclined to ask, “How could school X move up/down so much?” the answer is:

bar exam performance and employment outcomes

bar exam performance and employment outcomes

bar exam performance and employment outcomes

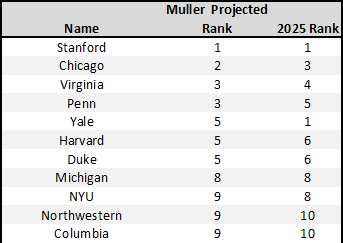

Here are the early projections.

Of some note is that there is less volatility than in previous years. As the two-year average of scores settles in for a second consecutive year, and as some of the jostling around the change in methodology settles down, we should expect some more stability. Of course, there is no guarantee these factors remain the same next year. And of course, significant swings in peer reputation score can always affect individual schools (some schools have seen more volatility in recent years).

Methodological notes: Any mistakes are my own. Where there are ties, they are sorted by score (e.g., if several schools are tied at the score of 35, the first-listed school has the “highest” score and the last-listed school has the “lowest” score), which is not reported here. But that is a huge caveat. A small rounding error could move a school from, say, 24th to 29th, but in my “score” they might actually only move from 28 to 29. My efforts to replicate the USNWR rankings may appear to introduce additional errors in volatility. On data collection, I occasionally transpose some schools due to inconsistencies in how the ABA reports school names. Schools beginning with Chicago, Saint, South, University of California, or Widener are most susceptible to these inconsistencies. Schools with alternative pathways to bar licensure are likely to see more volatility than most because of the complexities in evaluating them. Additional complexities, such as the “merger” of Penn State’s two law schools, could further complicate any analysis.