Ranking law school employment outcomes for the Class of 2024 using a Principal Component Analysis

A wide variety of employment outcomes can be simplified and offer a useful evaluation of law schools

One of the great challenges in assessing law school employment outcomes is that there seems to be some subjectivity in assessing “good” and “bad” outcomes. This could be mitigated through, say, survey data of students (e.g., “are you satisfied with your employment outcome,” etc.), but we do not have that data, and it may well reflect idiosyncratic revealed preferences of law students.

But another approach is to use a Principal Component Analysis (“PCA”). Professor Rob Anderson introduced this methodology in 2014 and revisited such a methodology in 2016, and I thought I’d revisit the project. This time, however, I used ChatGPT to help develop the rankings.

The best and worst job outcomes, and their weights in a ranking

The ABA’s law school employment outcomes outcomes disclose dozens of categories: Big Law jobs, federal clerkships, government jobs, JD Advantage, solo practice, unemployment, and more. Each category says something about how well a school’s graduates are doing, but trying to rank schools across these many job types is messy.

PCA takes all of that complexity and boils it down to a single score that captures the overall quality of a school’s job outcomes. It looks at each of these scores and tries to figure out where they converge and where they diverge to create a single line through them all.

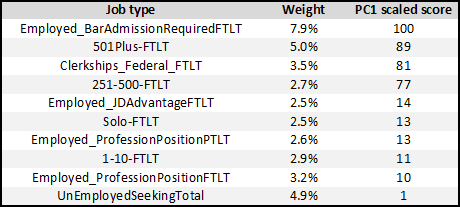

The top 10 categories of jobs, in terms of their weight in the overall PCA score, are in the chart below. Additionally, the “quality” of each of those job positions is given a scaled score from 1 (low) to 100 (high).

The raw overall full-time, long-term, bar admission required* category is number one, a scaled score of 100, and a whopping 7.9% of the weight in the PCA (whopping, because there are dozens of job categories in the ABA disclosures!). *Note: the ABA now labels these positions as “bar admission required” instead of “bar passage required” (BPR), apparently because many graduates, and perhaps increasing numbers, are “admitted” to the bar through diploma privilege or alternative pathways to licensure instead of “passing” a bar exam. Sadly, the acronym BAR instead of BPR may increase confusion in the future.

Unsurprisingly, several categories immediately follow as highly associated with those positions: employment in the largest law firms (firms with at least 251 attorneys make the top 10 at scaled scores of 89 and 77) along with federal clerkships (scaled score of 81).

At the bottom, the worst outcome is “Unemployed and Seeking,” 4.9% of the weight in the PCA, and the lowest scaled score (1). Unsurprisingly, it is diametrically opposed to full-time, long-term, bar admission required jobs. Positions highly correlated with the worst employment outcome include solo practitioners or placement in firms with 10 or fewer attorneys; employment in JD Advantage jobs; and employment in “professional” jobs.

These are not to say these are “bad” outcomes per se (e.g., a Harvard graduate working for Goldman Sachs or McKinsey is in a “JD advantage” position). But it is to say, these categories are highly correlated with unemployed students. They are also inversely correlated with positions in full-time, long-term, bar admission required positions. It appears that “professional” or “JD advantage” positions are substitutes for bar admission required jobs. Likewise, working at very small firms is correlated with schools having higher unemployment rates.

Now that we can assess these many categories and how they relate to one another, how do law schools stack up against one another?

A law school ranking for the Class of 2024 employment outcomes using PCA

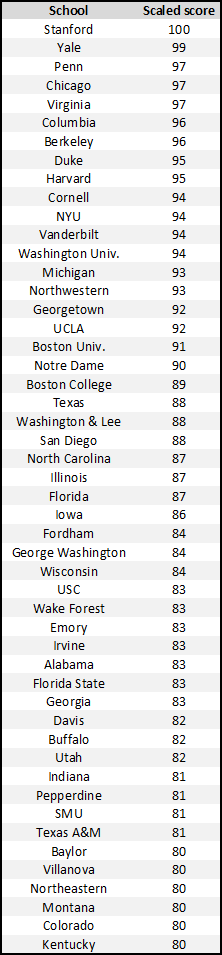

The analysis takes all these jobs and tries to figure out what are “good” and “bad” outcomes and compares the categories against each other. It then allows us to see the overall relationship between the jobs on a single scale. Here are the top 50 schools from the Class of 2024 employment outcomes, with the top school receiving a 100 score.

Many elite schools have similar outcomes, so it is no surprise to see many schools clustered around the 90-100 score band. There are few surprises among the top schools. But some schools, like San Diego, Buffalo, and Northeastern, significantly outperform what one might expect from the USNWR law school rankings. Recall, this analysis tries to measure the overall quality of employment outcomes, so overperformance or underperformance in any one job category cannot explain the outcomes. It is really the sum of the parts of the employment outcomes.

Now, of course, there are even caveats with this data. As I mentioned, the Harvard Law graduate going to McKinsey or Goldman Sachs is a different kind of "JD advantage” job than many might secure. A federal clerkship for a “feeder” appellate judge on the DC Circuit is different than a regional magistrate judge clerkship. Wachtell has “only” 265 attorneys and does not fit the 501+ category of employment. The list goes on.

But, on the whole, you can see how PCA helps us sort through the many messy categories of employment toward a more holistic view of employment outcomes.

How does this compare with the USNWR methodology for employment?

What PCA tells us about the USNWR methodology

USNWR ranks law schools on a several criteria, but the biggest category by far is employment outcomes. USNWR gives “full weight” to five kinds of outcomes:

Full weight was given for graduates who had these 45 types of jobs [sic]. The 100% weighted jobs were those who had a full-time job that lasted at least a year and for which bar passage [sic] was required, or a full-time job that lasted at least a year where a J.D. degree was an advantage.

Plus, we give full weight to school-funded full-time, long-term fellowships where bar passage is required or where the J.D. degree is an advantage. We also give full weight to those enrolled in graduate studies in the ABA employment outcomes grid.

“Full-weight” to “bar passage required” jobs fits the “a job is a job” approach that USNWR has had for this category—there is no weighting for sub-categories of employment. It’s the best indicator for law school outcomes in our PCA.

But JD advantage jobs, as Professor Anderson noted more than a decade ago, do not fit this category of high quality outcomes. It is a category that ought to receive some lesser weight in the overall rankings. (The other three categories are more marginal in the aggregate, although funded jobs tend to positively correlate with outcomes and graduate degrees negative, and given that these categories are highly manipulable for individual schools even if they do not much affect the aggregate is another, separate consideration.)

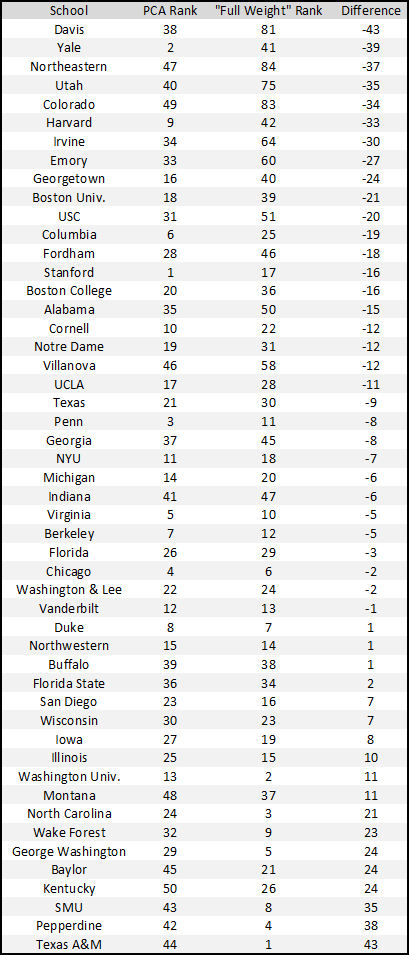

While USNWR weighs other positions with some lesser value, “full weight” jobs (as I’ve written a term that only makes sense as a label for USNWR rankings) are a reflection by USNWR that these positions are the “best” outcomes. So how do these 50 schools compare if their rank in the PCA scores are placed up against their rank in “full weight” outcomes?

The University of California-Davis suffers the most in the USNWR methodology compared to its PCA score, placing just 81st in the “full weight” employment ranking but a much strong 38 in the PCA. Yale and Harvard likewise underperform substantially. Of course, many schools perform about the same in the overall ranking. But because employment is such a heavy component of the USNWR rankings, even slight variances matter.

In short, the USNWR methodology cannot be justified by more objective criteria like PCA. PCA consistently indicates that JD advantage jobs should receive lesser weight. PCA also uses a much more sophisticated approach to the data to refine the different types of jobs in a way to identify the strengths of many of the most elite institutions, and to identify some higher-quality employment outcomes in other schools that USNWR otherwise overlooks.